Wildflower of the Year 2022 Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Buttonbush is a shrub or small tree commonly attaining heights up to about 6 m, occasionally twice that size. Leaves are opposite or whorled, elliptic to ovate, 2-8 cm wide, and 6-15 cm long; margins are entire and apices are acute or cuspidate, i.e., with an abrupt, short, tooth-like point. Triangular stipules, 2-3 mm long, are located between petiole bases and have marginal gland-tipped teeth. Flowers are borne in densely crowded globose heads, 2-3.5 cm in diameter, located at the ends of stems and from leaf axils near stem tips; flowers may be found through the summer, but are most abundant in June and July. Individual flowers are sessile: four green sepals are fused to form a short calyx that sits atop the inferior ovary, from which also emerge four white petals fused into a gradually widening tube about 1-2 mm in length, and terminating in four rounded lobes. Staminal filaments are fused with the corolla tube; anthers are positioned between corolla lobes near the mouth of the corolla tube. Styles up to about 4 mm in length extend well beyond the corolla tube and terminate in elongate-capitate stigmas. Fruits of individual flowers are dry, indehiscent nutlets; collectively, fruits of an inflorescence form a compact woody ball; eventually, individual fruits split apart where the two carpels are joined, and single-seeded half-fruits are dispersed.

In the Garden

Buttonbush is adaptable to a variety of garden settings, from shallow standing water to moist or moderately moist soils and full sun or part shade; it will not do well in persistently dry soil or dense shade. The plants respond well to pruning and old plants can be rejuvenated by cutting stems to the ground in spring. Buttonbush can be propagated most easily by softwood cuttings in spring or by hardwood cuttings in fall; seed requires no pretreatment, but germination rates may be low and seedling plants establish more slowly than cuttings. When flowering, Buttonbush is widely acknowledged as a “pollinator magnet”; it has lovely burgundy fall color, and its persistent fruit clusters provide winter interest.

Name & Relationships

Cephalanthus occidentalis was named by Linnaeus in his seminal work Species Plantarum; the genus name combines Greek words for “head” and “flower,” in reference to its globose inflorescence; “occidentalis” means “western,” North America being well to the west of Sweden, Linnaeus’ home country. The genus consists of six species found in temperate and tropical regions of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Cephalanthus is classified in Rubiaceae, a large and diverse family of plants.

Human Uses

Buttonbush contains a number of bitter-tasting and potentially toxic alkaloid molecules. In small doses, it has been used medicinally by Native Americans to treat a wide variety of ailments. Beekeepers value the plant because it produces an abundance of floral nectar. Buttonbush can be used to control erosion along margins of lakes, ponds, and streams.

Where to See It

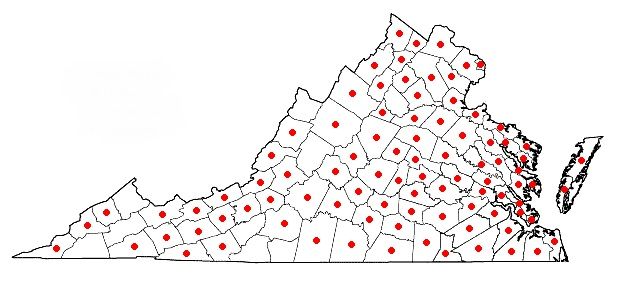

The native range of Buttonbush extends from southern Canada and New England south to Florida and eastern Texas, and further south into portions of Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. In addition, the species is found in the Great Valley of California and in several states of the southwest U.S. where moist canyons support its need for water. Although not yet documented in every county of Virginia, Cephalanthus occidentalis occurs throughout the state. Look for it in sunny sites near water.

In the Wild

When flowering, Cephalanthus occidentalis attracts a wide variety of floral visitors, including diverse species of butterflies, moths, bees, wasps, flies, and hummingbirds. Mallards, Wood Ducks, and Teal consume the seeds; songbirds like the Yellow Warbler and Common Yellowthroat are known to nest among its branches. Despite the presence of known toxins, deer will lightly browse the foliage.

Conservation Status

Cephalanthus occidentalis is common and abundant throughout its range.

Buttonbush Distribution – Digital Atlas of Virginia Flora

View or download the Buttonbush Brochure (PDF)

Gardeners should not collect Buttonbush in the wild and should be certain that all native plants purchased for home gardens have been nursery-propagated, not wild-collected. For retail sources of nursery-propagated plants and responsibly collected seeds, visit https://vnps.org, email info@vnps.org, or call 540-837-1600. To see and learn more about interesting species of plants native to Virginia, visit https://vnps.org and contact your local chapter of VNPS (https://vnps.org/chapters) for times and dates of programs and wildflower walks in your area.

Text by W. John Hayden, VNPS Botany Chair

Color illustration by Elena Maza Borkland

Color photos by W. John Hayden and Nancy Vehrs

You may already be aware but, while paddling in the City of Martinsville reservoir I observed quite a few buttonbushes. I see by the map above that the plant is not native to Henry County nor is it marked as “introduced”.