Manage White-Tailed Deer to Protect Our Natural Heritage

Most residents of Virginia understand the need to change human land use practices to stop or minimize habitat destruction and preserve our native plant communities. An increasing number of people also support combating the spread of non-native invasive species to include problem plant species and insects such as the emerald ash borer beetle which girdles ash trees wiping out most trees in the genus Fraxinus across large land areas.

These two conservation priorities remain tremendously important, but there is a critical need to add another: controlling populations of white-tailed deer.

White-tailed deer, (Odocoileus virginianus), are beautiful animals, part of the natural fabric of North America, adaptive and graceful. Deer are prey species, requiring predators to keep their populations in check. Without predators removing at least 40% of a deer herd per year, deer populations quickly grow and they eat more of the plants, nuts and seeds than an ecosystem can sustain. “Ecological carrying capacity” is the term for the point at which the number of organisms in a species become so abundant that they alter the ecosystems they live in. White-tailed deer have exceeded theirs.

Left: Forest with healthy understory Right: Over-browsed forest with no understory ~Photos by Charles Smith

Humans arrived in North America over 13,000 years ago. We, not wolves and mountain lions, gradually became the top predator controlling populations of large herbivores. Many of those species eventually went extinct. Due to over-hunting, white-tailed deer nearly joined their ranks by about 1900.

In the mid-20th century, Virginia joined many other states in reintroducing white-tailed deer to supplement the few deer left and increase numbers for sport hunting. As reintroductions were carried out from the 1930s to the 1980s, two things happened that greatly contributed to the increase in the number of deer.

First, land use shifted away from agriculture toward suburban and urban uses. Contrary to commonly held beliefs, suburban landscapes do not take away deer habitat – they create it. Deer are adaptive animals. Suburban development creates preferred edge habitat for deer, and human landscapes provide high concentrations of edible plants close to the ground where the deer can get to them. You can grow more deer in suburbia than you can in a purely forested landscape. The same is true in rural areas where forests are broken up by agricultural fields, pastures, house lots and powerline easements.

The second major factor was a shift in how people view and interact with wildlife. As the 20th century progressed, more people lived in suburban and urban areas, and the number of people hunting dropped off, so there was reduced hunting pressure on deer herds. In 1942 the movie Bambi was released by Walt Disney. This film has influenced generations of Americans into believing that man is bad and all human interventions in nature are harmful. We now know how wrong the premises of that movie are. When you prevent fire from periodically visiting our natural areas and do not control large herbivores like deer, all species suffer and our natural heritage is impoverished.

Deer are a prey species that requires predation to control their populations. Without predation they can double their numbers in as little as one year. With abundant food in rural and suburban landscapes, and almost no hunting pressure in suburban areas and declining hunting pressure in rural areas, deer numbers have skyrocketed state-wide. In many areas of the state, deer population numbers are at more than three to eight times the densities that native plant communities can sustain.

I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer. And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades.

-Aldo Leopold, Thinking Like a Mountain

Biologists began to notice impacts from excessive deer browse in some parts of the country as early as the 1940s. Research began in earnest in the 1970s. Staff from the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries estimates that the Virginia deer herd numbers about 1 million animals. White-tailed deer are large herbivores, needing about 5 pounds of forage a day, with each animal eating about a ton of leaves, shoots, twigs, seeds and nuts per year. That equates to over a million tons of Virginia’s biota being converted to deer biomass per year. There are more deer and less of everything else.

This is happening across the state, a widespread filter of browsing animals steadily impacting our native plants. If left unchecked, deer browse will remove hundreds of plants and thousands of insects and dozens of small animals that depend on them. The losers include orchids, trilliums, oaks, milkweeds, hickories, blueberries and many other plants that provide food and shelter to numerous insects and birds.

Losers to Deer Browse. Top left: Yellow ladyslipper orchid (Cypripedium parviflorum), Top right: False Solomon’s seal (Maianthemum recemosum), Bottom left: Four-leaved milkweed, (Asclepias quadrifolia), Bottom right: Indian cucumber root (Medeola virginiana) ~Photos by Charles Smith

Over-browsed forest with monoculture understory of unpalatable ferns. ~Photo by Charles Smith

The winners include a shortlist of native plants such has hay-scented fern and a long list of invasive plant species that support few other species. The difference is one between a native landscape with numerous wildflowers through spring and summer, abuzz with activity, compared to a simplified green landscape, devoid of colorful flowers and the sound of forest dwelling birds – an impoverished environment.

Henry Wilbur, retired Professor of Botany at the University of Virginia, has been working for the past nine years to show the correlation of deer browse to native plant decline in controlled experiments at the Mountain Lake Biological Research Station in Giles County, Virginia. Professor Wilbur and his colleagues demonstrated that over an eight year period, deer browse began to reduce the total number of plant species and dramatically reduced the size, abundance and ability to reproduce for most of the forest herbaceous plants. This research shows that plant energy reserves are decimated as they try to grow with repeated browsing. Further research will be done to determine the rate at which these plants go extinct in a forest stand over time.

Researchers from Cornell University found that deer browsing not only removes many native plants from the forest ecosystems, but alters the seed bank so that those species cannot return and forest succession is impacted for hundreds of years. (DiTommaso, Antonio, et al; 2014.)

The result is that our remaining forest ecosystems are decimated. Deer eat everything native with few exceptions. They eat almost all of the non-woody plants in the forest as well as all shrubs and trees within their reach as well as the majority of the acorns and hickory nuts. They have now removed most vegetation from many of our forests below 5 feet.

The impacts include the loss of many of our woodland wildflowers, a change in forest stand composition to a few species such as tulip tree, American beech and red maple that have smaller seeds and appear to be less palatable to deer, and the disappearance of up to 75% of our forest bird species in many areas due to loss of the understory that provides them cover and the insect species they rely on for food.

Deer promote the spread of invasive plant species by transporting the seeds on their coats, hooves and in their feces, eliminating competition from native plants and disturbing soils. As our forests are oversimplified we lose native species, and once the existing trees die, there will be little to replace them except the few native species that deer find unpalatable and non-native species that provide little ecological benefit.

In 2008 the USDA Forest Service began to make dire predictions about eastern forests due to the over-browsing by white-tailed deer. The problem is so severe that even if we could reduce the number of deer immediately to within ecologically sustainable levels, it would take many decades if not centuries to recover our native plant communities.

If we act soon we can retain enough native plant stock and seed that many species could recover within remaining forests and repopulate surrounding areas over time.

This is even more critical in the face of climate change in the expected shift of species and communities across the landscape.

So what are we to do about it? Forest management professionals, advocating for the sustainable use and management of forest resources were clear: “To do this, white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) populations must be low enough to allow for the regeneration of forests and the development of desired plant communities and wildlife habitats.” (The Michigan Society of American Foresters 2006.)

To reduce the number of deer, people generally raise the prospects of reintroducing large predators, sterilizing deer or administering birth control to curb population growth, and using lethal control methods to include hunting and sharpshooting.

♦Predators – Attempts at reintroducing wolves in the western United States (gray wolves) and North Carolina (red wolves) have met significant resistance. Reintroducing large predators to the densely populated eastern United States is not viable. In addition, humans have been the dominant predator of white-tailed deer for at least 13,000 years.

♦Immunocontraception – Three studies have been undertaken in closed deer populations (those confined to islands or fenced compounds) to determine whether using contraceptives on deer would be effective at lowering populations. In all three (Fripp Island, SC; Fire Island National Seashore, NY; and National Institute for Standards and Technology, MD) there was some success in reducing the reproductive rates, but deer populations were never reduced below 100 to 200 deer per square mile – between five to ten times the ecological carrying capacity for eastern forests. (Rutledge, August 2012)

♦Sterilization – Efforts to sterilize white-tailed deer have demonstrated that although there could be some localized reduction over time, sterilized females remain in estrus, attracting more males in the near term and potentially increasing deer-vehicle collisions; sterilization programs would need to be preceded by lethal reduction of herds in advance to bring populations to more manageable levels (Boulanger, 2012); and multiple studies show that deer move in and out of study areas frustrating herd reduction efforts even in fenced compounds. (HSUS, 2013) (City of Fairfax, 2014)

♦Lethal Control – Monitoring of vegetation in areas where hunting has occurred over multiple years using various methods has demonstrated that lethal control of deer can result in recovery of herbaceous plants and production of large numbers of seedlings of woody plants. (Jenkins, 2014) (Author’s observations at Conway Robinson State Forest, Gainesville, VA)

Lethal control methods are the only deer population control option that have been shown to be effective. It is time for residents and local governments throughout Virginia to join with the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, the Virginia Natural Heritage Program, large landowners and managers and others in supporting and urging efforts to reduce and manage the number of white-tailed deer in order to protect our native plant species, the communities in which they live and the animal species that depend on them.

The measure as to whether management efforts are successful must be based on recovery of our native flora which is the foundation for our natural communities. The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries is working with Virginia Tech to develop such a measurement tool. Efforts to measure impacts in long-term studies such as those at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, UVA’s Mountain Lake Biological Research Station, and College Woods near Lake Matoaka at the College of William and Mary will be critical for not only monitoring forest change and the impacts of deer browse, but also whether management efforts are successful.

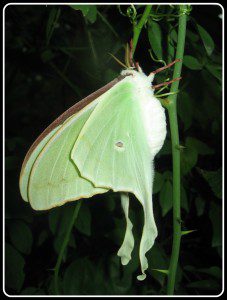

Another loser to Deer Browse: Luna moth, (Actias luna) ~Photo by Charles Smith

The conversation needs to shift from deer to plants. We need to have fewer deer so we can have more of everything else – more native plants and the myriad of organisms they support. Call me selfish. I would rather share the land with a diverse assemblage – see trailing arbutus, thimbleweed and lady-slipper orchids; hear the call of ovenbirds.

Charles Smith

VNPS Co-Registry Chair,

PWWS Conservation Chair,

Naturalist

Charles is a native of Virginia. He has a masters degree in Environmental Science from George Mason University, and a bachelor’s degree from the College of William and Mary. Charles served in the United States Army Infantry. He is a natural resource management professional with twenty three years experience in natural resource inventory, monitoring and restoration, to include fifteen years experience in deer management. Charles speaks to diverse audiences on topics ranging from native plants to ecological restoration, and is an instructor for three chapters of Virginia Master Naturalists.

“The current [deer] density is producing devastating and long-term effects on forests. Foraging deer “vacuum up” the seedlings of highly preferred species, reducing plant diversity and in the extreme, creating near mono-cultures. It could take decades or even hundreds of years to restore forests. . . . Deer have the capacity of changing forest ecology, by changing the direction of forest vegetation development. It doesn’t matter what forest values you want to preserve or enhance—whether deer hunting, animal rights, timber, recreation, or ecological integrity— deer are having dramatic, negative effects on all the values everyone holds dear.”

-Stephen Horsley, US Department of Agriculture Forest Service Researcher

(“The forest nobody knows.” Forest Science Review. Newtown Square, PA: USDA Forest Service Northeastern Research Station; Winter 2004(1), p. 4. http://www.fs.fed.us/ ne/newtown_square/publications/FSreview/ FSreview1_04.pdf. 29 May 2007).

Literature Cited:

Boulanger, Jason R., et al; Sterilization as an alternative deer control technique: a review; Human–Wildlife Interactions 6(2):273–282, Fall 2012.

City of Fairfax 2014 Sterilization Program Annual Report as provided to the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries.

DiTommaso, Antonio, et al; “Deer Browsing Delays Succession by Altering Aboveground Vegetation and Belowground Seed Banks;” PLOS ONE, Volume 9, Issue 3, e91155, March 2014.

Ellis, Bob, Editor; Virginia Deer Management Plan 2006-2015, Wildlife Information Publication No. 07-1; Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Wildlife Division, June 2007.

Horsley, Stephen, US Department of Agriculture Forest Service Researcher;“The forest nobody knows.” Forest Science Review. Newtown Square, PA: USDA Forest Service Northeastern Research Station; Winter 2004(1), p. 4. http://www.fs.fed.us/ ne/newtown_square/publications/FSreview/ FSreview1_04.pdf. 29 May 2007.

Humane Society of the United States (HSUS); 2010, 2012 and 2013 Progress Reports [of the] Immunocontraception of White-tailed Deer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland.

Jenkins, Lindsay H., et al; “Herbaceous layer response to 17 years of controlled deer hunting in forested natural areas;” Biological Conservation, 175, pp. 119–128, 2014.

Leopold, Aldo; “Thinking Like a Mountain;” A Sand County Almanac, p. 137; Oxford University Press, 1949.

Michigan Society of American Foresters 2006. Position statement on white-tailed deer in Michigan. http://michigansaf.org/Business/ PosStates/Deer.htm; 29 May 2007.

Rawinski, Thomas J.; “Impacts of White-Tailed Deer Overabundance in Forest Ecosystems: An Overview;” Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture Newtown Square, PA www.na.fs.fed.us ; June 2008.

Rutberg, Allen; Fact Sheet: PZP Immunocontraception for Deer; Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine; August 2012.

Wilbur, Henry, PhD; “Oh Deer: How Perennial Woodland Herbs Survive the Overabundance of Whitetails;” Summary of research on white-tailed deer impacts on woodland herb species at the University of Virginia’s Mountain Lake Biological Research Station in Giles County, Virginia from 2006 to 2014; a presentation at the Virginia Native Plant Society annual winter workshop at the University of Richmond, March 7, 2015.

Superb, well researched and written article, Charles! Thanks for bringing this issue to the forefront and underscoring the urgent need for action in managing deer overpopulation.

Best article I’ve seen about controlling deer populations–and I’ve read many. We run a managed hunt in a community of 196 landowners, each of which owns 5 acres plus. This is incredibly labor intensive (need hunting permission from landowners, need to locate & mark hunting sites, need to communicate, communicate, communicate with landowners) but we are fortunate to have access to hunters already vetted by local county governments who run Managed Hunts. After 7 successful years (beginning population 174/sq mi down to about 60/sq mi after a couple of years), the understory is beginning to return as are some of the invasive aliens (Japanese honeysuckle, Vinca, English Ivy). Some of the wildflower species are returning although orchids, for example, have not.

There was a change in management this last season in the 8th year with few deer taken. We are looking for new, easier ways to organize the managed hunt.

Deer depredation is way up this winter, even before the fawns have been born. We are adjacent to a National Park that is not removing deer. With new park management and more NPS experience in sharpshooting, we hope to improve the situation.

This tropic suggests managing the white-tailed deer to protect national heritage in where its populations must be low enough to allow for the regeneration of forests and the development of desired plant communities and wildlife habitats. However, I do not agree to this point as i believe, nature is good enough to curve this problem.

While it is clear that deer overpopulation in VA and elsewhere is a serious threat to forest and forest edge diversity, the prevailing VA Dept. of Game & Inland Fisheries Deer Management Plan goals & objectives (been around since March 2007) are not mentioned or addressed in this article. I find not including this document and its steering principles from a cadre of state and federal experts a blow to the Chicken Little conclusions drawn by the author. The concept that forests in general and deer populations cannot live amicably and in reasonable balance is highly suspect. Most (12.8 million) of Virginia’s 15.8 million acres of forestland and edge habitat is privately owned, and more than 373,600 individuals/families hold

a total of 10 million acres. These private holdings average less

than 75 acres in size, but range from a few acres to thousands

of acres. How is wholesale deer reduction using lethal means truly feasible on the vast majority of private lands? Virginia’s deer harvest in 2014 was just under 195,000 deer, and doesn’t consider those deer that died from accident, injury, disease, and predation. And harvests are declining, adding to the pressure.

Thank you for your comments.

Indeed, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) has experienced and talented staff overseeing the management of deer in Virginia. The fourth document cited for this article is the Virginia Deer Management Plan 2006-2015. That document was used for information on deer biology, population numbers and the basic approach to population control: “This is a strategic plan (e.g, proposing regulated hunting as the preferred method to control deer populations).” (p. 2)

Indeed, the article expresses support for VDGIF. The Virginia Deer Management Plan also states: “Currently, deer management objectives aim to limit or stabilize populations over much of Virginia. This represents a change in direction regarding deer management, from an initial effort to establish and expand the deer herd to one of controlling population growth. Deer population management is based on the concept of cultural carrying capacity – the number of deer that can coexist compatibly with humans.” (p. 12)

VNPS members are working closely with staff from VDGIF and other principal stakeholders to bring attention to the fact that the traditional perspective of looking at Biological and Cultural Carrying Capacities is insufficient. These are relicts of the North American Hunting Model which was developed to manage deer for sport hunting and also seeks to minimize human-deer conflicts. This approach does little to address the larger problem – ecological damage and alteration of our forested ecosystems.

This can only be addressed by using Ecological Carrying Capacity for white-tailed deer and the health of our native plants and the communities they comprise as the measure that matters. Without healthy native plant communities, ecosystems unravel. It is about the plants.

Making this change is a huge paradigm shift that VDGIF staff have engaged in. But they need support. They have many stakeholders that do not understand the ecological issues and/or are primarily focused on managing huntable populations. VDGIF’s funding comes from licensing fees for hunting and fishing. They need support to educate their constituency and put into place new methods to measure ecological impacts change the approach to deer management. I work with many hunters who have embraced their new role as population and ecosystem managers, and we need to expand their ranks.

The statements in this article are not “Chicken Little conclusions” but facts based on over four decades of research by thousands of professionals. Deer are a keystone species that is decimating our remaining forest lands. There is no magic balance of nature in this situation where man can remain removed and everything will be OK. Deer are a prey species and they require a predator to control their populations. Their populations are out of control and are decimating our forests. This will not change without a lot of people understanding the need to manage deer and participating in the process.

As for whether it will be feasible, that is a great question. If we are to restore our ecosystems, we must manage deer. If we are to manage deer, they will need to be controlled across large land areas in multiple states. There are some good and hopeful examples of localized reductions that have resulted in recovery of non-woody flowering plants and recruitment of young trees and shrubs. This will need to be replicated widely.

I hold out hope. The human population of Virginia between 1800 and 1900 rose from 800,000 to 1.8 million. During that time humans extirpated deer from most of the state. The human population of Virginia is now over 8 million. We have the numbers, the difference is that most people are disconnected from the land and do not see deer as food. That is our challenge: to educate and engage people to gain their support and participation. Only through hunting will we recover our flora.

The upcoming Capitol Region Invasive Pest Symposium will focus on Whitetail deer management plans in place throughout Northern VA. Capital Region Invasive Pest Symposium

Monday, March 23, 2015 from 9:15 AM to 1:45 PM (EDT)

Triangle, VA

To Register: http://www.eventbrite.com/e/oh-deer-strategies-for-white-tail-deer-management-tickets-15746155174

Protecting natural resources is good…but, more fundamentally, how about protecting our local food supply? Small farmers are threatened by the deer population as well as the natural habitat. We are part of that habitat too.

[…] Source Article: https://vnps.org/manage-white-tailed-deer-to-protect-our-natural-heritage/ […]

I believe Charles’ rebuttal explanations are credible and well thought out. The other comments in addition, are correct: something proactive must be done about deer to protect habitat and the systems supported in them. Desirable organic farming and small operators are getting decimated by deer browse damage. As Charles points out, and as evidenced by my own residential setting, suburban environments are increasingly giving rise to larger herds of herbivores which have no real predators, and the populations wherever they occur in excess are exceeding carrying capacity. Deer are seemingly everywhere, even in places no deer would normally occupy. Deer must be managed and controlled.

Excellent, well-researched article Charles. Thank you!

Join Walt Carson, Associate Professor of Plant Community Ecology at the University of Pittsburgh, on March 27, 2015 – 3:30 pm – at the Rock Creek conference room at the National Zoo (Research Building at the National Zoo) for a presentation entitled “On the Causes and Consequences of Region-wide Changes in the Browsing and Disturbance Regimes Within the Eastern Deciduous Forest Biome”.

Free to the public.

[…] More at https://vnps.org/manage-white-tailed-deer-to-protect-our-natural-heritage/ […]

I understand that you can apply for a nuisance permit and cull (kill)deer on your property. Who are the proper authorities to contact?

Sue, we have contacted Charles for an answer, it may take a day or two, but please check back.

Hi Sue,

There are three main programs sponsored by the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries designed to cater to deer management at the property or landscape level: 1) the Deer Management Assistance Program (DMAP), 2) the Damage Control Assistance Program (DCAP), and 3) the Deer Population Reduction Program (DPOP). DMAP and DCAP permits are issued at the property level and provide additional tags to take antlerless deer during the regular hunting season. The goal is to liberalize the taking of does to reduce the population or at least curb its growth. DPOP, also called kill permits, are issued to take unlimited antlerless deer any time of the year. DPOP permits are harder to get, but that often depends on your region of the state and how it is viewed in terms of population reduction by VDGIF staff.

See: http://www.dgif.virginia.gov/wildlife/deer/deermanagementprogram.asp

Information on and an application for the DMAP can be found at:

http://www.dgif.virginia.gov/wildlife/deer/dmap.asp . Information on DCAP can be found at http://www.dgif.virginia.gov/wildlife/deer/dcap.asp . For those permits, you can work directly with your District Wildlife Biologist.

For DPOP or kill permits, you will need to talk to your local VDGIF Conservation Police Officer (formerly game wardens). Contact numbers for Conservation Police Officers by region can be found at http://www.dgif.virginia.gov/enforcement/.

The minimum property size for the DMAP program is 2 acres. You can lump properties together to qualify for the acreage limit, and this can also help if firearms use for deer management in your area of the state is limited by the size of the property.

I hope this is helpful.

Charles

Are pink lady slippers endangered in central VA?

Joan, here is a link to the plants that are currently listed by the the Virginia Department of Natural Heritage:

http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/natural_heritage/documents/plantlist14.pdf

There are three species of Cypripedium that ARE listed: Showy-ladies slipper, Kentucky-Ladies slipper, and Small-white Landies slipper. The Cypripedium commonly called Pink Ladies slipper is not currently listed. Thanks for asking and caring!

I am a sharpshooter – I took my grandson to hunting classes as I wanted him to have a proper attitude and be able to down a deer causing as little pain as possible. The men in the class laughed and joked about drinking, some can’t hit the deer except in the leg or butt and are too lazy to follow it to take it out of its pain. I was totally disappointed in the attitude, lack of compassion, smart alecness of some of the men. So to prevent the abuse of the deer are you testing the men to make sure they are sharpshooters, do they drink while hunting etc etc.are they respectful of wildlife?????

Emily, we certainly share your concern, and your disappointment. We ourselves, of course, have nothing to do with the classes you are talking about; and we strongly suggest that a letter outlining your experience be sent to the public officials who are in charge of the program in the location you attended. Thank you for your comment, and for your motivation to provide your grandson with a good model to follow in his hunting education.

Charles, Kudos on your thorough and clear explanation of the need to reduce deer populations to ecological carrying capacity.

Sue, Charles answered your question about permits for harvesting deer on your property. But you do not need a special permit. Landowners can hunt deer on their own property or allow others to hunt without either of the special permits. In fact, State law allows landowners (including tenants) and their families to hunt on their land without obtaining a hunting license. However, I suggest everyone who hunts take the Hunter Safety Course and support the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries by purchasing licenses even if not legally required.

Jerry Peters, Potowmack Chapter

I’m a forestry consultant that works in the Piedmont of the Carolinas. I think the growing coyote population here is a positive development that could help control populations. I’ve witnessed coyotes pursuing full grown deer and see the signs (remains) of the predation of fawns. Unfortunately, almost every hunter I encounter kills coyotes on sight. Some have even brag about the specialized guns and calls they’ve purchased for killing them.

Here (South Carolina) we have the state actively encouraging the killing of coyotes: http://www.dnr.sc.gov/wildlife/coyote/. They’ve even put out a bounty on them with prizes awarded: http://www.thestate.com/news/local/article111820862.html

Educating the public (and evidently the state wildlife commissions) would be a start. Regrettably, public opinion is hard to change, and the wildlife commissions and state legislatures have a financial incentive to maintain high deer populations. So-called “outdoorsmen” buying licenses, hunting supplies, ATVs, and trucks brings millions into the economy. It’s hard to put that kind of value on a trillium or lady slipper, at least for 99% of the population.

Tim, thanks for your thoughtful comment. It is hard, but it’s possible, to educated the public; and it’s certainly one of the priorities of our Society. Greater public awareness of the importance of native plants and the need to protect pollinators are examples of the way opinion can be influenced. We have to keep trying, because what is the alternative?

Like you, we will keep appreciating those trilliums, and keep up the efforts to get people out there to enjoy, and thus value them along with us. We also value the effort you are making – every bit counts!